MarketWatch

The numbers: Yet another increase in the cost of living in September kept the rate of U.S. inflation at a 30-year peak, adding to mounting evidence that prices are likely to remain high well into next year.

The consumer price index climbed 0.4% last month, the government said Wednesday. Higher prices for food, gasoline and rent drove most of the advance.

Economists polled by The Wall Street Journal had forecast a 0.3% increase.

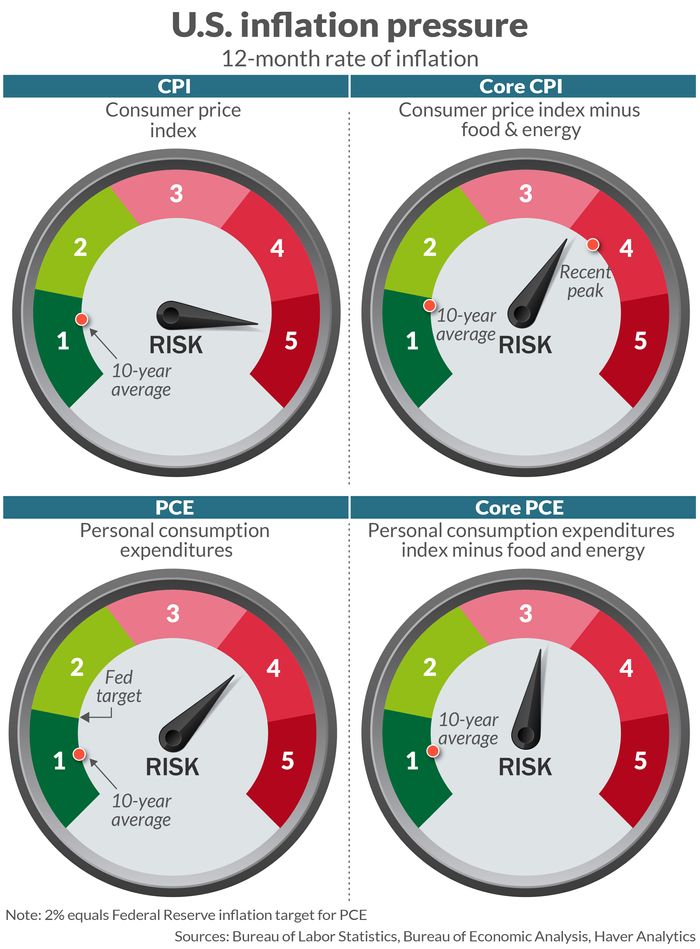

The pace of inflation over the past year, meanwhile, edged up to 5.4% in September from 5.3% in the prior month. That’s more than double the Federal Reserve’s 2% average target.

Consumer prices have risen this year at the fastest pace in three decades, setting aside a brief oil-driven spike in 2008.

Another closely watched measure of inflation that omits volatile food and energy costs rose 0.2% last month. This so-called core rate is closely followed by economists as a more accurate measure of underlying inflation.

The 12-month increase in the core rate was unchanged at 4%. It had reached a 30-year high of 4.3% in June.

Big picture: The big surge in inflation this year is likely to last well into 2022 — an outcome the Federal Reserve has only recently acknowledged.

Broad shortages of labor and supplies are raising costs for companies and they are charging customers higher prices to maintain their profits. These shortages in some cases have gotten worse and there’s little end in sight.

The ongoing bottlenecks have forced the Fed to reconsider its view that inflation was “transitory” and would fade by the end of the year.

Chairman Jerome Powell recently conceded inflation would stay higher for longer than he had expected. And Atlanta Federal Reserve President Raphael Bostic said central bank officials should stop calling inflation transitory.

The upshot: The Fed to set to announce in November that it will begin to withdraw stimulus for the U.S. economy.

Some Fed watchers also think high inflation could force the central bank to move up its first increase in interest rates, but that remains to be seen. A key short-term rate has been near zero since early in the pandemic.

Key details: The cost of gasoline rose 1.2% in September and was a big contributor to the increase in inflation last month.

What’s worse, oil prices are still on the rise and that could nudge inflation even higher in October.

The cost of food surged almost 1% last month, mostly for groceries. Grocery prices have climbed 4.5% in the past year and are increasing three times faster than they did in the five years before the pandemic.

The cost of rent, meanwhile, jumped 0.5% in September to mark the biggest increase in 20 years.

A nationwide eviction moratorium ended last month and rents have been rising steadily over the past year. Shelter is the largest expense for most families.

Prices also rose for car insurance, education, recreation and phone and Internet service.

Prices fell for airline fares, hotel rentals and several other services after a surge in delta cases toward the end of summer. Americans opted to travel less until the caseload began to decline.

The cost of used cars also fell, though prices are still sky-high compared to a year earlier. Soaring used-vehicle prices played an outsized role in the surge in U.S. inflation earlier this year.

Sifting through the details of the report, there’s little evidence prices pressures will ease soon.

Increases in energy and food prices show little sign of letting up. The cost of rent is likely to continue to rise. And medical prices have been unusually subdued, a trend that won’t last, economists say.

The ongoing shortages of business supplies — parts and materials — also strongly suggest prices are unlikely to relent.

What they are saying? “Inflation isn’t coming down quickly anytime soon,” said corporate economist Robert Frick of Navy Federal Credit Union.

“Extended supply chain disruptions —and potentially further increases in energy costs — are likely to maintain a hot inflation trend through yearend and into 2022 even as pandemic effects slowly ebb,” said senior economist Ben Ayers of Nationwide.